All Music •

All Music •  Album of the Year (95%) •

Album of the Year (95%) •  Discogs •

Discogs •  Freebase •

Freebase •  Jazz Music Archives •

Jazz Music Archives •  Music Brainz •

Music Brainz •  Rate Your Music (4.25 / 5) •

Rate Your Music (4.25 / 5) •  WikiData •

WikiData •  Wikipedia

Wikipedia .png) Pitchfork •

Pitchfork •  Prog Archives

Prog Archives

All Music •

All Music •  Album of the Year (95%) •

Album of the Year (95%) •  Discogs •

Discogs •  Freebase •

Freebase •  Jazz Music Archives •

Jazz Music Archives •  Music Brainz •

Music Brainz •  Rate Your Music (4.25 / 5) •

Rate Your Music (4.25 / 5) •  WikiData •

WikiData •  Wikipedia

Wikipedia .png) Pitchfork •

Pitchfork •  Prog Archives

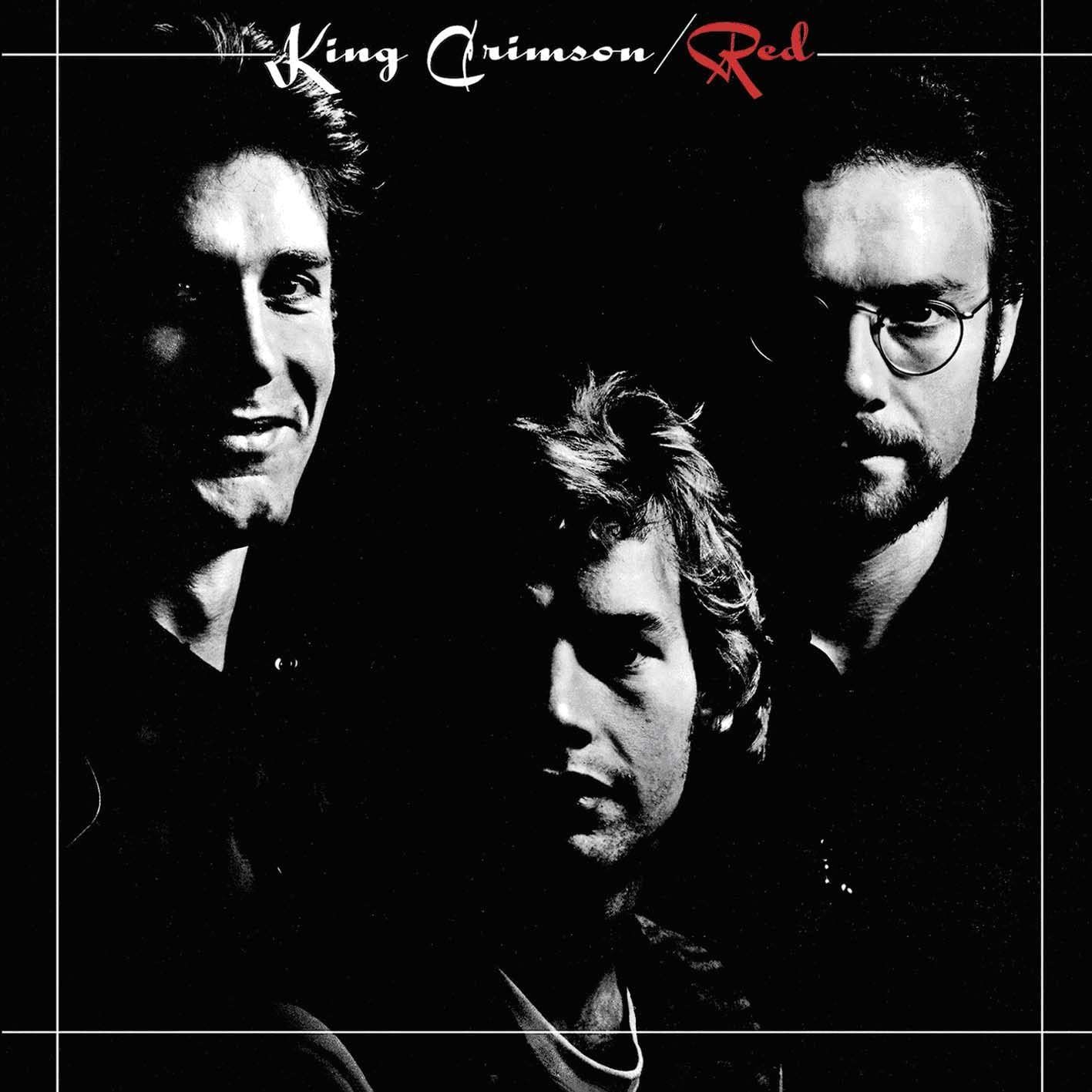

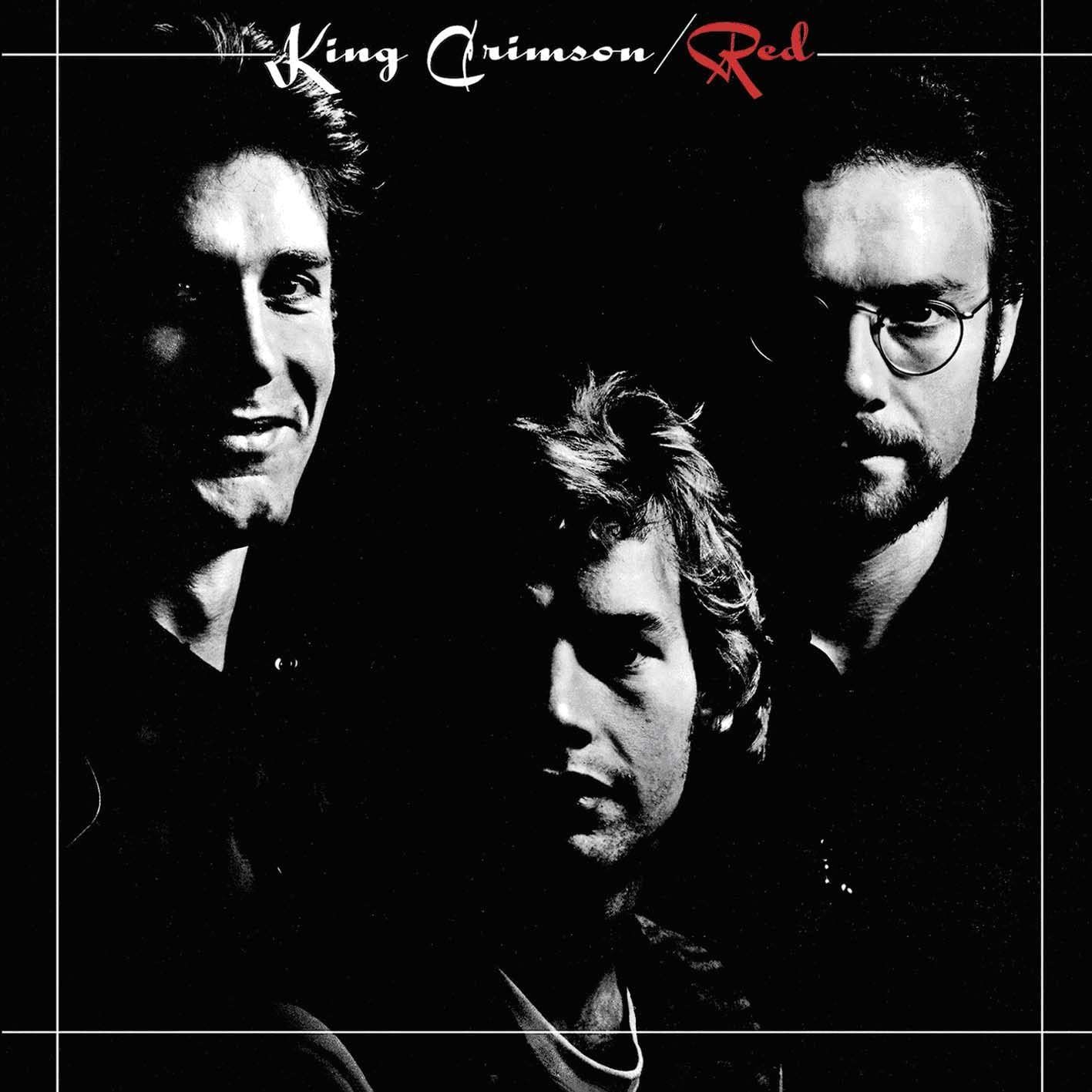

Prog Archives While it would serve as the band’s final statement of the decade, Red, released in the autumn of 1974, does not sound like a eulogy. It’s vicious and vital, bristling with energy and new ground to cover. It stands as one of classic rock’s heaviest, most meticulous albums. It was equally influential for Kurt Cobain and Trey Anastasio; as seminal for metal as it was for math rock; equally beloved by scholars and stoners. With a dark, meditative sheen, it also lays the groundwork for Fripp’s more atmospheric work to come: music that influenced an entire field of artists diametrically opposed to everything he helped popularize in progressive rock.

Red is a record about fear. Its five songs are fiery and anxious, visceral and bold. The whole band (Fripp, bassist/vocalist John Wetton, and drummer Bill Bruford) were growing weary of one another, but they remained deeply attuned to their emotional climate. In “One More Red Nightmare,” a crashing airplane is a metaphor for entrapment, as Bruford rides against a busted-up cymbal he found in a trash can. It sounds like an accident, like scrap metal colliding in the sky. “Fallen Angel,” a ballad that’s alternately sweet and threatening, makes direct reference to gang violence in New York. It’s the first King Crimson lyric that could be called topical.

”Providence,” an improvised piece recorded live at their ’74 tour stop in the city of the same name, appears as the penultimate track on Red. Sequenced between the screaming “One More Red Nightmare” and the closing “Starless,” the song might seem like a quiet reprieve, but it builds to its own creeping intensity, like the scene in a horror movie when the protagonist finds a place to hide that turns out to be a trap. The performance is led by Cross’ violin, chased by Wetton’s distorted bass. When the whole band comes crashing in, it feels violent, even fatal. This was Crimson going off-script, no longer following the letter of the prog law but letting their instincts and their emotions run the show.

If “Providence” was the tortured sound of Crimson falling apart, the title track is their holy union. “Red” is effervescent, crushing, endlessly ascending. The song defines what Bruford calls the band’s “thick, intelligent Metal kind of sound,” making prominent use of the tritone, a Crimson melodic signature that signals dissonance, something lurking in the background (think: the “Twilight Zone” theme). The band had played at being sinister before, but “Red” was the first time that Crimson themselves sounded like something to be scared of. It’s a constant climax, a frightening rush of adrenaline.

“Starless,” the closing track on Red, was the swan song for Crimson’s ‘70s era and the finest song the group would ever record. In live versions, its central motif—a sad, hummable refrain—was performed by Cross on violin. On record, Fripp plays it on guitar, soaring with the same weightless sheet metal bend he later brought to “Heroes.” Wetton’s lyrics, meanwhile, are crushing in an imagistic way, delivered solemnly, like the national anthem for an imagined country. During its climactic breakdown, as Wetton’s bass buzzes with Geezer Butler levels of menace, Fripp plays a series of unison notes paired on two strings, climbing up the fretboard until the tension can no longer hold. Then, the band blasts off into a rapturous finale, in 138 time no less.

“Starless,” the closing track on Red, was the swan song for Crimson’s ‘70s era and the finest song the group would ever record. In live versions, its central motif—a sad, hummable refrain—was performed by Cross on violin. On record, Fripp plays it on guitar, soaring with the same weightless sheet metal bend he later brought to “Heroes.” Wetton’s lyrics, meanwhile, are crushing in an imagistic way, delivered solemnly, like the national anthem for an imagined country. During its climactic breakdown, as Wetton’s bass buzzes with Geezer Butler levels of menace, Fripp plays a series of unison notes paired on two strings, climbing up the fretboard until the tension can no longer hold. Then, the band blasts off into a rapturous finale, in 138 time no less.

There are a lot of ways to hear Fripp’s solo during the breakdown in “Starless.” Sometimes it sounds like a mockery of the tedious gymnastics that had come to define prog rock. 1974 was, after all, the year that Yes toured their 80-minute slog Tales From Topographic Oceans in its entirety, giving naysayers an 80-minute excuse to abandon the genre altogether. It was also the year that Genesis released The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway—their final album with frontman Peter Gabriel—taking their sound to theatrical, conceptual extremes. “Starless,” in its way, was Crimson’s own self-immolation. With his solo, Fripp suggests stasis, a growing nausea, an explosion of monotony, as the band swarms around him like vultures. Bruford taps on bells and scratches cymbal heads as Wetton’s bass increases in volume and agitation. All the while Fripp sits on his stool, riding forward, one note at a time. You don’t know how much more he can take. Then, he finds a way out.